A Family Tradition

These days, historic sites are popular places to hold weddings -- especially if there’s a site that’s significant in someone’s family history. From ancestral houses to famous gardens and hotels, museums and important cultural spots have become sought-after locales for that special day.

That wasn’t quite the case when longtime Historic Christ Church volunteer Nancy Clark was planning her wedding in 1955. “People thought it was terrible for me to be married at Christ Church,” she said in a 2015 oral history she gave as part of the Tidewater Main Street Development Project. The objections didn’t stem from the fact that she chose a historic church, but rather from the way the church was situated. “They’re high-back pews,” Nancy explained, and many of her guests “were afraid they wouldn’t see anything. They liked to go to a wedding where they could see all the pretty dresses.”

But Nancy was determined to be married in a church that meant so much to her family. Her mother was a member of the Altar Guild, while her father was on the vestry (“like many of the local families,” Nancy told the interviewer) – but most importantly, her grandmother, Ann Ball Carter, had also been married in Christ Church, over fifty years earlier in 1902. It would take careful planning, since at the time the church wasn’t in regular use and only opened for special services, but Nancy’s tenacity eventually won the day.

It was a beautiful wedding to make anyone proud. A relative sang, while all the music was accompanied by the church’s pump organ. “In those days,” she remembered, “the ushers would come in with this roll of white, what they call, tracking, and roll it down the aisle, so that when the bride came in, she would be walking on this white rug.” Two years earlier, Nancy had traveled to Europe with friends and had been convinced to buy a Brussels lace veil and a fan. She included both in her wedding day ensemble.

Nancy’s choosing to walk down the aisle at Christ Church created an interest that had far-reaching effects. Other women began choosing to be married there as well, leading to the creation of The Bride Book, the church’s pictorial archive of each wedding held thereafter. But more personally for Nancy, her own daughter decided to continue the tradition, wearing Nancy’s dress and veil in her own Christ Church wedding in 1988. (Contributed by HCC&M Research Committee Member Shaune Lee)

Smallpox inoculation in Northumberland County - 1768

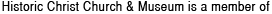

This advertisement for smallpox inoculation from John Smith of nearby Indian Creek in Northumberland County appeared in the Virginia Gazette on June 9, 1768. Doctors like Smith inoculated patients by placing small pieces of infectious matter in their arms and quarantining them until recovery.

Smallpox killed 10-30% of its victims and often left survivors blind or disfigured. Inoculation began in Boston in 1721 and spread to Virginia by the 1750s-1760s.

Robert “King” Carter called the disease a “fatal distemper to his countrymen.” When his son John contracted it while studying in London in 1717 Carter expressed his shock over what he called “this cruel discouragement to an English education.” Carter hoped that John would recover and then “’twill rejoice me that he had it.”

Six decades later, Carter’s grandson Robert Carter III, sick with a “Fever Heat” while in quarantine following an inoculation for smallpox, experienced what he called a “most gracious Illumination” that sparked a dramatic religious odyssey that saw him embrace first the Baptist faith and in his later years the teachings of Swedish mystic Emanuel Swedenborg. Robert Carter III’s religious journey played a critical role in his 1791 Deed of Gift, which ultimately emancipated over 500 enslaved people Carter owned on plantations in the Tidewater and Shenandoah.

A smallpox outbreak struck Williamsburg in the fall of 1747, lasting about a year. Read more here: Encyclopedia Virginia | Colonial Williamsburg | History of Smallpox

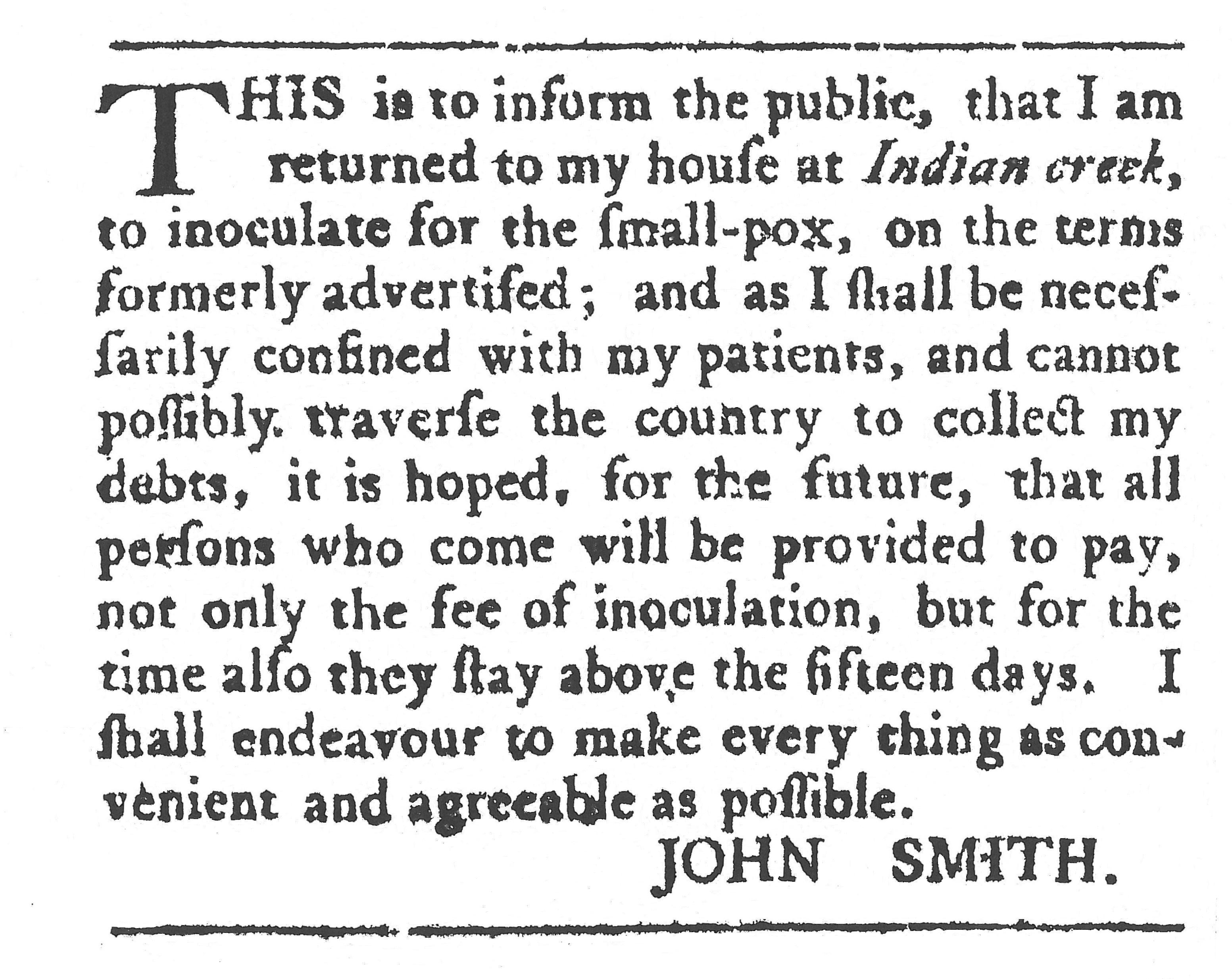

Corotoman Neck Precinct, Christ Church Parish - June 10, 1746

This detail from a chart compiled on June 10, 1746 by Lancaster County Court justice Dale Carter was from a tithable list. In colonial Virginia a tithable was a taxable person, someone on whom a head of household paid taxes (to the parish, county or colony). The colony’s legal definition of who was tithable changed several times over the seventeenth century. In its revision of the laws in 1705, Virginia established that all males age sixteen and over and all black, mulatto, and Indian females age sixteen and over who were not free were tithable. Virginians reported their tithables every June 10. Carter compiled the names and total number of tithables per household in Corotoman Neck, one of six precincts in Christ Church Parish, Lancaster County. Corotoman Neck had 65 households and 260 tithables, 168 of whom were enslaved. 46 households (71%) owned enslaved people.

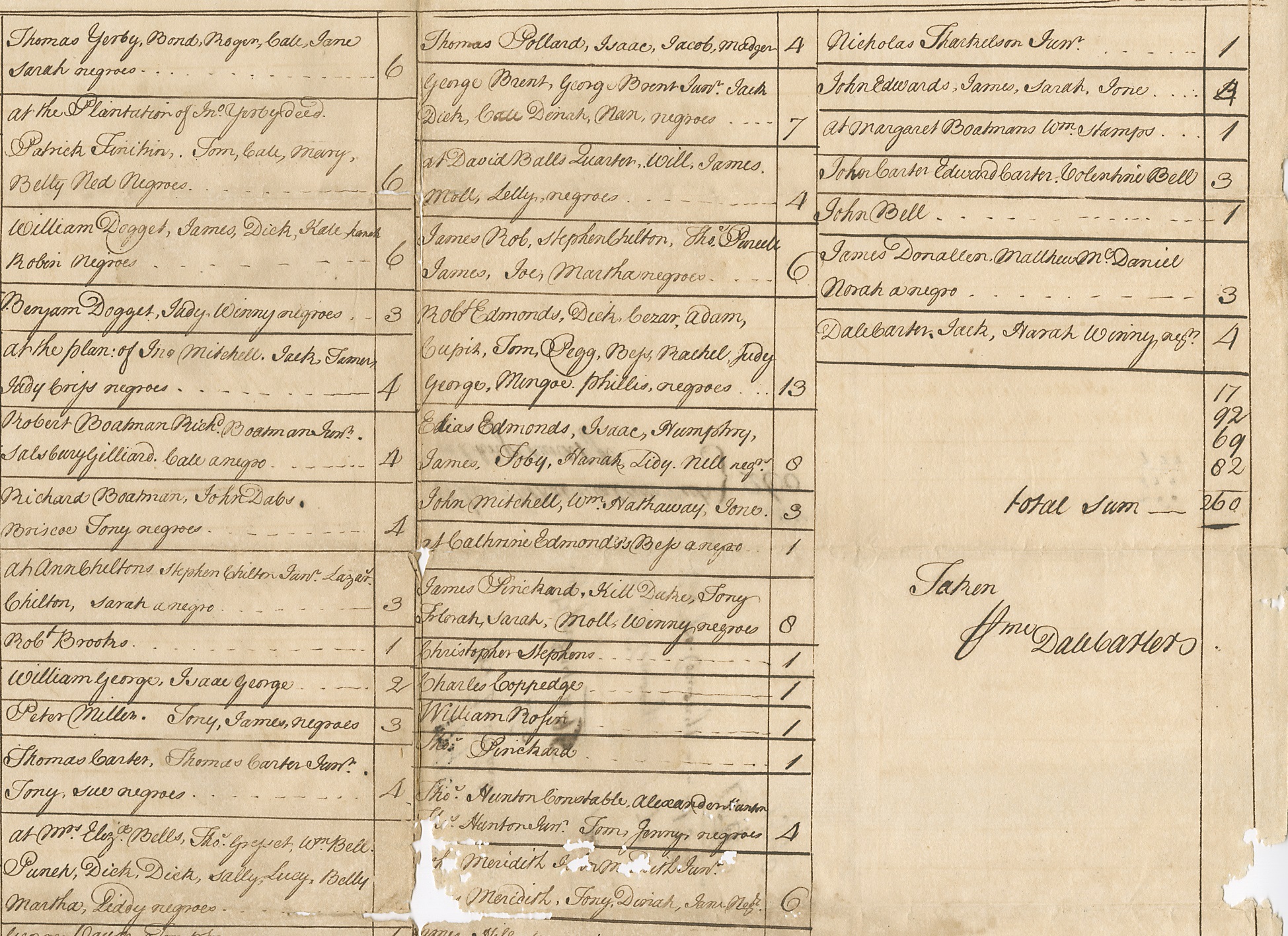

Election Day for Lancaster County - December 2, 1768

This election return records Lancaster County’s votes for the House of Burgesses on December 2, 1768. By Virginia law, each county selected two men to serve in the House of Burgesses, who with the Governor and the Governor’s Council comprised Virginia’s General Assembly.

Elections did not take place annually or even regularly; they usually occurred following the governor’s dissolution of the Assembly and call for a new one or the death or resignation of a burgess. Directed by a writ from the governor and his Council, the county sheriff posted notice of the election date at courthouses and ordered that the notice be read in parish churches in the Sundays leading up to the election.

The right to vote in colonial Virginia was limited to freeholders, or white males who owned certain amounts of land either outright or through a lifetime lease. By 1736 Virginians had to own at least 100 acres of unimproved land or 25 acres of improved land for at least one year before an election.

Sheriffs conducted elections at the county courthouse. There was no private ballot: freeholders cast their votes aloud, directly in the presence of candidates who employed clerks to record the poll. In a practice known as “treating,” candidates often provided alcohol and food to voters, both opponents and supporters, before (legal if done before the sheriff announced the writ calling for elections) and after elections but even on election day itself.

On this day in Lancaster County, voters elected Colonel James Ball and Charles Carter to represent them in Williamsburg. Note that the first two names recorded under Ball’s and Carter’s polls were those of the local clergymen: Church of England minister David Currie and Presbyterian minister James Waddell.

Learn more here: Encyclopedia Virginia: Elections in Colonial Virginia

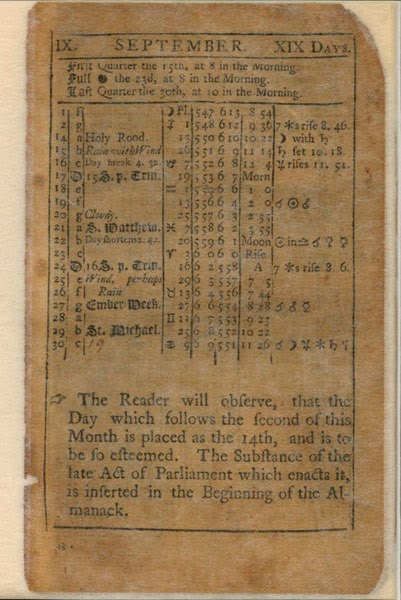

England and Virginia adopt the Gregorian Calendar - September 14, 1752

When Virginians woke up on September 14, 1752, they must have felt like they had been asleep for eleven days. Well—not exactly.

Up to that point, England and its American colonies were still on the Julian calendar, first implemented by Julius Caesar in 46 B.C. In 1582 Pope Gregory XIII introduced the Gregorian calendar to correct deficiencies in the Julian calendar that affected the timing of seasonal equinoxes and Easter. Unlike Spain, Portugal and other Catholic countries, Protestant England held on to the old calendar.

In 1751, citing “divers[e] inconveniences,” “frequent mistakes” and “disputes” arising from the two calendars, Parliament passed the Calendar Act. This act authorized adoption of the Gregorian calendar and moved the beginning of the new year to January 1 instead of March 25, which England had recognized (legally) as the first day of the year since the 12th century. Dates between January 1 and March 24 often were written like this: January 9, 1722/23.

By this point, the Julian calendar was 11 days off from the Gregorian calendar and the true solar year. To remedy this, the Calendar Act declared that September 2, 1752 would be followed by September 14.

So Virginians and people in the American colonies and England indeed went to bed on September 2 and woke up on September 14. Ben Franklin for one found virtue in the switch, reporting that “It is pleasant for an old man to be able to go to bed on September 2, and not have to get up until September 14.”